Harriet Beecher Stowe, author and abolitionist, was deeply moved by the inhumane conditions of slavery. Having talked with slaves who escaped across the Kentucky-Ohio border, she was compelled to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851), a novel that furthered the development of abolitionist sentiment within the country. Through her passionate writing, the men, women, and children who suffered under slavery were personalized in a way that raised awareness and created compassion.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, author and abolitionist, was deeply moved by the inhumane conditions of slavery. Having talked with slaves who escaped across the Kentucky-Ohio border, she was compelled to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851), a novel that furthered the development of abolitionist sentiment within the country. Through her passionate writing, the men, women, and children who suffered under slavery were personalized in a way that raised awareness and created compassion.

One would not expect her to come to the South so soon after the Civil War, but she chose Mandarin as her winter home in 1867. She first assisted her son Frederick as he began a cotton farm operation at “Laurel Grove” (now Orange Park) in Clay County. They had to row across the St. Johns to pick up the mail in Mandarin, and it is said that she fell in love with the area and wanted it for her winter refuge. Though she was not welcomed by all in the area, in 1873 she wrote, “I came to Florida the year after the war and held property in Duval County ever since. In all this time I have not received even an incivility from any native Floridian.”

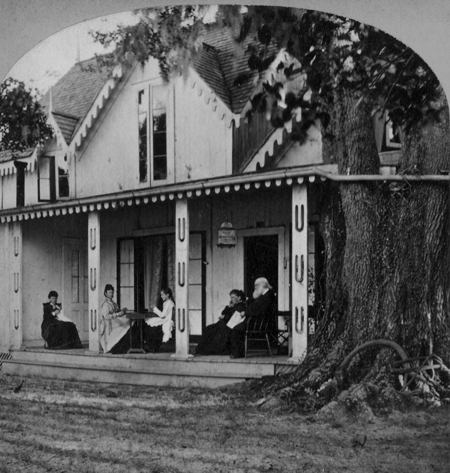

Her “cottage” was on the river just east of the location of today’s Mandarin Community Club. It became a meeting place for Bible studies taught by her husband Calvin, often meeting on the large front porch facing the river. Oranges from her grove were shipped to the North on the local steamships. She was very active in community life. Her family helped organize the Episcopal Church of Our Saviour, and she was instrumental in convincing the Freedmen’s Bureau to build a school for African-American children in Mandarin. She and her daughters even organized and acted in plays performed in the community. Her stories about Mandarin appeared in Northern periodicals and are compiled in her book Palmetto Leaves (1872), and later in Calling Yankees to Florida – Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Forgotten Tourist Articles (2013), edited by John T. Foster, Jr. and Sarah Whitman Foster. Her articles are credited with boosting the winter tourist industry in Florida because of her lovely descriptions of the temperate winter weather, the live oaks, Spanish moss, orange blossoms, fruit and flowers in Florida.

Her “cottage” was on the river just east of the location of today’s Mandarin Community Club. It became a meeting place for Bible studies taught by her husband Calvin, often meeting on the large front porch facing the river. Oranges from her grove were shipped to the North on the local steamships. She was very active in community life. Her family helped organize the Episcopal Church of Our Saviour, and she was instrumental in convincing the Freedmen’s Bureau to build a school for African-American children in Mandarin. She and her daughters even organized and acted in plays performed in the community. Her stories about Mandarin appeared in Northern periodicals and are compiled in her book Palmetto Leaves (1872), and later in Calling Yankees to Florida – Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Forgotten Tourist Articles (2013), edited by John T. Foster, Jr. and Sarah Whitman Foster. Her articles are credited with boosting the winter tourist industry in Florida because of her lovely descriptions of the temperate winter weather, the live oaks, Spanish moss, orange blossoms, fruit and flowers in Florida.

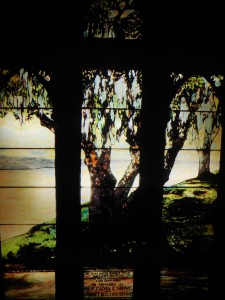

Stowe’s fame was phenomenal. Her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a best seller and was, and continues to be read by people in countries all around the world. Many say that she is the most famous person to ever live in Jacksonville, let alone Mandarin. People would travel to Mandarin to catch a glimpse of her on her porch and later to see the Stowe Memorial Window installed in the Church of Our Saviour.

The Stowes left Mandarin for the last time in 1884 when the strain of age and ill health became too much for Calvin to travel the long distance. When they left Mandarin, Mrs. Stowe requested that the Church of Our Saviour erect a window on the river side of the church in honor of her husband. Finally, in 1916, a splendid stained glass window was commissioned to Louis Comfort Tiffany, a great admirer of Harriet Beecher Stowe. The window was of a secular nature, depicting her view from the porch of her home, and included the oak trees, moss, and the river that brought so much pleasure to the Stowes while they were in Mandarin. The window was dedicated to Calvin and Harriet together. Sadly, in 1964 the window was destroyed by a hickory tree that fell down directly on it during Hurricane Dora. A display of the window (pictured at right) and selected fragments are on view in the permanent exhibit in Mandarin Museum.

The Stowes left Mandarin for the last time in 1884 when the strain of age and ill health became too much for Calvin to travel the long distance. When they left Mandarin, Mrs. Stowe requested that the Church of Our Saviour erect a window on the river side of the church in honor of her husband. Finally, in 1916, a splendid stained glass window was commissioned to Louis Comfort Tiffany, a great admirer of Harriet Beecher Stowe. The window was of a secular nature, depicting her view from the porch of her home, and included the oak trees, moss, and the river that brought so much pleasure to the Stowes while they were in Mandarin. The window was dedicated to Calvin and Harriet together. Sadly, in 1964 the window was destroyed by a hickory tree that fell down directly on it during Hurricane Dora. A display of the window (pictured at right) and selected fragments are on view in the permanent exhibit in Mandarin Museum.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Litchfield, Connecticut in 1811 and died in Hartford, Connecticut in 1896. She and her husband, Reverend Calvin E. Stowe, are buried at the historic Phillips Academy Cemetery in Andover, Massachusetts.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe Center on Stowe’s life

- Southern Cultures article on Stowe’s time in Mandarin, Shana Klein

- Replicating Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Experiences in Florida, John T. Foster, Jr.

- Florida’s Historical Markers: Harriet Beecher Stowe, The Florida Channel

- Harriet Beecher Stowe in Florida, Florida Frontiers TV